By: Shmuel Raz and David Breitkopf

Imagine a group of hunter-gatherers during the late Paleolithic era, standing atop a mountain ridge and gazing over a vast valley below. They are searching for a place to set up camp, and every choice could mean hours of travel and potential dangers. Their keen senses interpret information, allowing them to perceive essential cues. The distant blue of the horizon hints at water—a vital resource. Swaths of green suggest lush vegetation, promising food and shelter. Cloud formations act as natural weather maps, signaling impending rain or storms. In arid climates, the glint of waxy leaves from afar indicates prolonged drought and areas prone to fire. Animal behaviors provide additional information: a sudden silence among birds might indicate predators, while flocks in flight could point toward abundant food sources.

These observations are not just passive sightings—they are part of a human perceptual reality finely tuned by natural selection over hundreds of thousands of years. Ancestors who could interpret these sensory cues survived and passed their perceptual abilities to future generations.

At the heart of this is the Natural Perception Hypothesis (NPH), defining perception as an evolved interpretation of sensory information. NPH posits that each species inhabits a unique perceptual world, shaped by natural selection. This concept builds upon Jakob von Uexküll’s idea of the Umwelt, describing how each organism perceives its surroundings based on its sensory capabilities and brain interpretation, as explored in the field of sensory ecology.

Consider humans and their trichromatic vision—the ability to distinguish red, green, and blue hues. This adaptation likely evolved to help ancestors identify ripe fruits and nutritious vegetation, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Sensory-Driven Evolution of Color Vision for Fruit Detection in Primates

Discerning subtle color differences provided a survival advantage, enhancing foraging success. As a byproduct, humans experience a richer array of colors—including the vibrant reds and oranges observed in natural phenomena.

In contrast, bees perceive the world through ultraviolet (UV) light, revealing patterns on flowers invisible to humans, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Ultraviolet Vision in Bees

These patterns often serve as nectar guides, directing bees to pollen and nectar, facilitating efficient pollination.

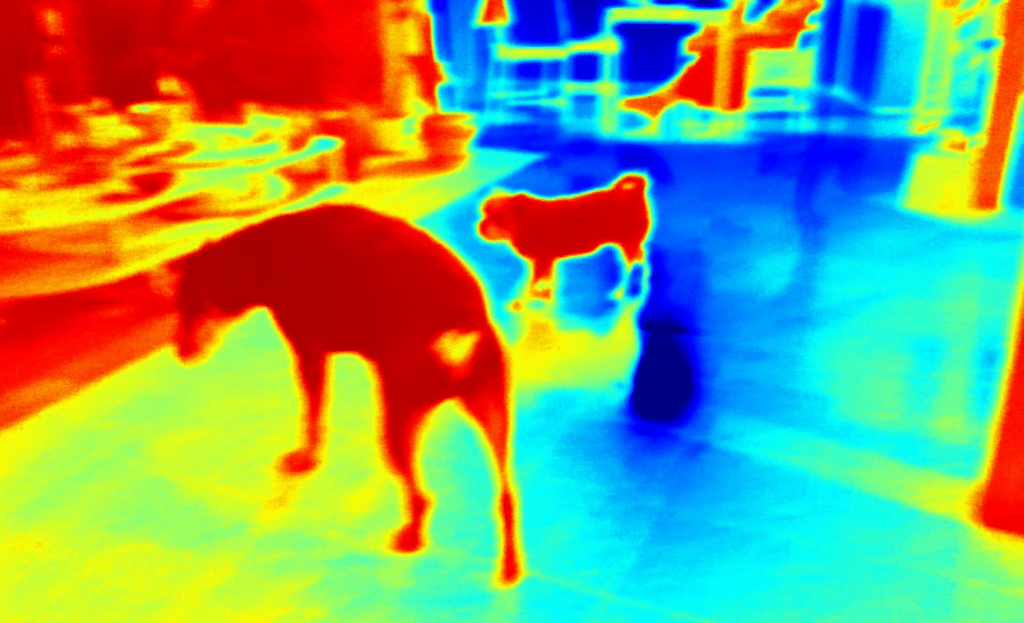

Similarly, pit vipers use infrared vision to detect the heat emitted by prey, as illustrated in Figure 4. Specialized pit organs allow them to sense thermal radiation, enabling effective hunting even in darkness. This adaptation opens up nocturnal niches that other predators cannot exploit.

Figure 4: Pit Vipers’ IR Vision

Sensory Adaptation, Species Formation and Our Perceptual World

Variations in sensory perception can lead to distinct environmental experiences, influencing behavior and habitat preference. Over time, these differences may cause populations to exploit different niches or develop unique mating rituals based on sensory cues. This divergence reduces interbreeding, leading to reproductive isolation. Eventually, these isolated populations may evolve into separate species—speciation. Thus, sensory adaptations shape individual interactions and can drive new species formation.

The NPH profoundly impacts our understanding of nature. The world as perceived through our adaptive sensory systems is uniquely human. No other species experiences nature exactly as we do, though overlaps exist with related species. This reframes how we perceive the environment, highlighting the intimate connection between perception and reality. Earth, as we know it, is a human-specific perceptual world, interacting uniquely with our sensory systems.

For example, the calming effect of green spaces may be linked to ancestral associations with abundant resources and safety. Birds singing might signal a secure environment free of predators. Even appreciation of natural beauty, like red sunsets, stems from sensory systems evolved for survival.

When the environment is harmed, not only are ecosystems damaged, but also the human perceptual world—essentially harming our perceptual potential. Since perceptions evolved to aid survival, we can attempt to reverse-engineer the meanings behind what we experience in nature. Much of human biology hasn’t changed significantly over thousands of years; sights, sounds, and smells often have roots in survival significance.

By studying how our perceptions of natural phenomena were once survival cues to our ancestors, deeper insights into our relationship with the environment emerge. This exploration is akin to assembling a puzzle where each sensory experience connects to survival history

The Beautiful Colors of Sunsets

The striking colors of sunsets did not directly influence survival; they are byproducts of evolving sensory systems. Trichromatic vision, developed for tasks like finding ripe fruits, incidentally allows humans to perceive stunning sunsets. This exemplifies how a change in a single sensory feature can simultaneously alter numerous interactions with the environment.

Conclusion

The Natural Perception Hypothesis offers a revolutionary view of how sensory adaptations shape evolution and biodiversity. It emphasizes that every species lives in its unique perceptual world—and that humans are one of these species—highlighting how we experience the world as an adaptive construct rather than objective reality. By appreciating the evolutionary roots of human perceptions, we can better understand our place in the world and the importance of preserving the environments that shape it.

Further Reading:

Raz, S., & Breitkopf, D. (2024). Natural Perception Hypothesis: How Natural Selection Shapes Species-Specific Sensory Experiences and Influences Biodiversity. Retrieved from https://dx.doi.org/10.17352/gje.000106

About the Authors

Shmuel Raz is a scientist and entrepreneur in the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University and the Institute of Perception in Western Galilee, Israel. His research bridges remote medical diagnostics, evolutionary biology and perception studies.

David Breitkopf, from the Institute of Perception, specializes in human perceptions shaped by cultural and religious traditions. Together, they explore how perceptions alter reality.

Published by: Josh Tatunay