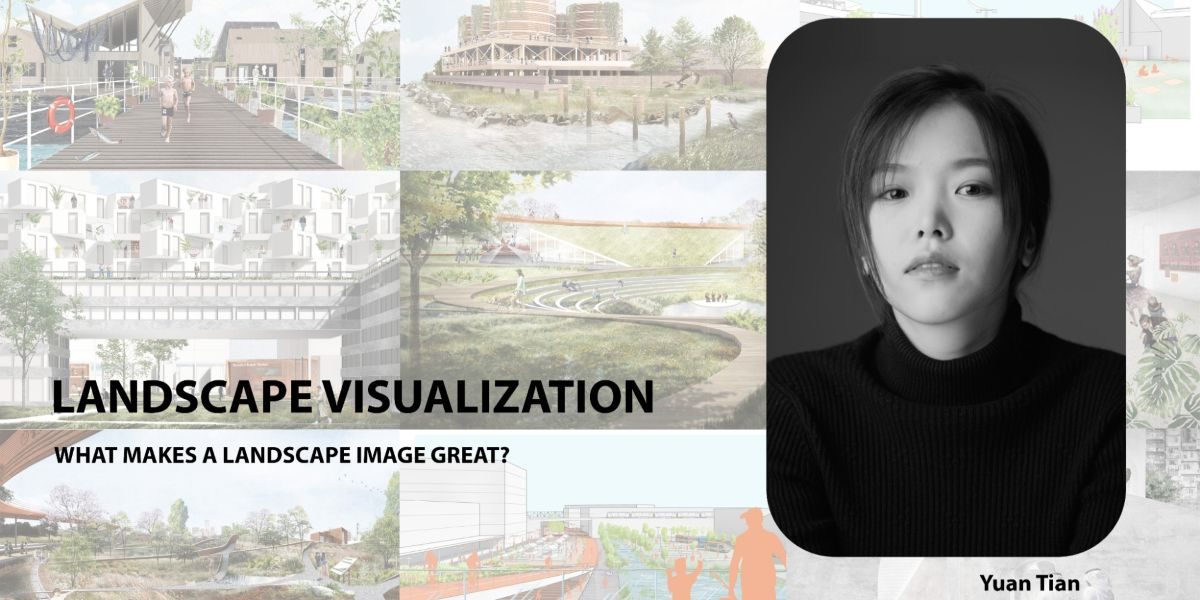

By: Yuan Tian

Yuan Tian is an award-winning landscape designer known for integrating ecological systems, cultural narratives, and climate resilience into her work. With experience ranging from waterfront resilience projects in New York with MNLA to her current role at RIOS in Los Angeles, Yuan applies a thoughtful, forward-looking approach to landscape architecture. Her design philosophy emphasizes emotional connection and practical skill-building, earning her recognition and a growing influence in the international design community.

1. The Art of Image-Making

A great landscape rendering goes far beyond technical representation — it invites the viewer into a world that doesn’t yet exist. It’s not just about showing what a space looks like, but about conveying how it feels to be there.

At its core, visualization combines three key pillars:

-

Photography Principles:

Point of view, framing, focal length, composition, and color balance — these create iconic, emotionally resonant images.

-

Modeling & Rendering Techniques:

Selective detailing, light and shadow, materiality and texture, thoughtful entourage and post-production together build a compelling visual story.

-

Communication Strategy:

The best images display emotion, suggest narrative, feature people and plants, and create atmosphere — they leave space for imagination.

2. What Makes Your Landscape Rendering Compelling?

When renderings perform at their best, they convey more than visuals — they evoke mood, atmosphere, and experience.

They can spark something dreamlike in the imagination, creating a longing for a place that hasn’t yet been built.

You can almost feel the warmth of the sun, hear distant conversations, or sense the shift from day to night.

As artist Walter J. Phillips once said:

“A landscape painting is essentially emotional in origin… it moves the hearts of others.”

To elevate your images, focus on four visual levers:

-

Composition

Composition is the foundation of a visually strong rendering. Aim for clarity and focus: every element should have a reason to be in the frame. Use the Rule of Odds, where three or five focal points create more interest than an even number. Balance your composition both horizontally and vertically, and make sure there’s a clear visual hierarchy that guides the viewer’s eye from one area to another. Try to avoid visual clutter and think of your scene as a story unfolding — what’s the protagonist of the image, and what’s supporting it?

-

Depth

Depth brings realism, emotion, and spatial understanding. Incorporate foreground, midground, and background elements to anchor your viewer inside the space. For example, a leaf in the foreground, a bench and user in the middle, and a tree line in the back can simulate how we perceive real environments. Atmospheric perspective — slight fading or desaturation of distant elements — can also help add dimensionality. A good sense of depth invites exploration, rather than just observation.

-

Color Temperature

Color temperature influences mood more subtly but just as powerfully. Warm light (sunset, late afternoon) often suggests comfort, intimacy, and vibrancy. Cooler tones (overcast, early morning) can convey calm, solitude, or even melancholy. Whichever palette you choose, be consistent: don’t mix warm and cool lighting unless intentionally creating contrast. Use color accuracy to make materials and planting believable, while still stylizing the scene to suit your design intent.

-

Light and Shadow

Lighting is one of the most powerful tools to evoke time and feeling. Think about the time of day you want to represent — dawn with long shadows feels entirely different from high noon or golden hour. Use shadows to emphasize material textures: the grain of wood, the layering of leaves, the roughness of stone. Light also directs the viewer’s focus — a spotlighted bench or glowing window immediately draws attention. Always ask: where is your light coming from, and what emotional tone does it set?

3. Use Images to Tell a Story

Great renderings are storytelling tools. They don’t just say “here’s a bench,” they suggest how someone might sit on it, what they might see, and how the space might come alive.

Add human figures that match the mood and time of day. Use vegetation to indicate climate and seasonality. Blur the line between realism and imagination — enough to be believable, but open-ended enough to inspire.

4. What Makes Landscape Visualization Unique?

Unlike architectural renders, landscape visualizations deal with living systems: plants, light, weather, human use over time. A building rendering can feel finished — but a great landscape rendering feels alive, always in flux, always inviting.

As landscape designers, we visualize spaces that change through seasons, grow with time, and are shaped by the people who use them. The magic lies in capturing that fluidity — and grounding it in emotion.

A rendering that touches the heart will always outshine one that only explains the design. So next time you hit “render,” ask yourself not just “does this look right?” — but also, “does this feel like a place someone would fall in love with?”

— Yuan Tian

Published by Liz SD.