By: John Glover (MBA)

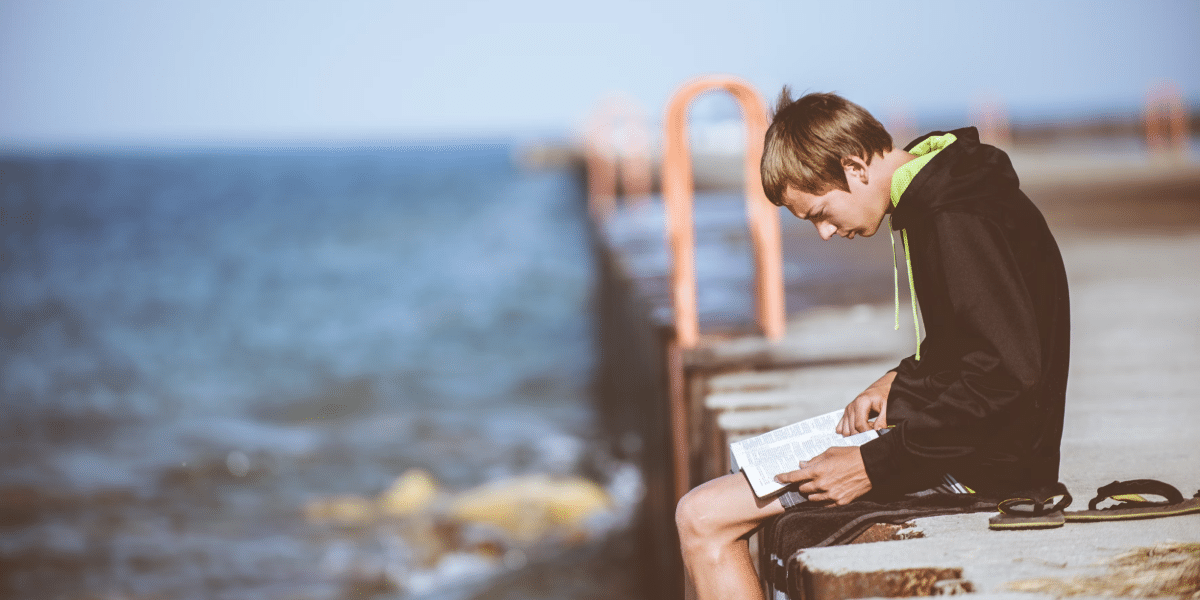

You’re getting dressed on a breezy autumn morning. You grab your favorite sweater, and as you pull it over your arms, you realize there’s a thread sticking out of the fabric. You contemplate pulling the thread. Once curiosity gets the better of you, you pull on the thread. You keep pulling and pulling, and before you know it, your sweater has begun to unravel. You try to rectify the situation – pushing the initial thread back into the fabric. Realization dawns on you: That one thread ruined your favorite sweater.

The temptation to use drugs is like the thread on your favorite sweater. It is sticking up – begging you to give it a slight tug. But, when you let that curiosity take over, you’re left with an addiction that is so detrimental to your life that a mere sweater will be the least of your worries.

As students return to school this month, parents expect to send their children off to gain an education, increase their knowledge and grow into beautiful people. The last thing they want their child coming home with is a drug addiction.

When evaluating the social dynamics of children and their friend groups, peer pressure seems to infiltrate it all. The desire to fit in, to be one with the masses, rather than an outcast, drives a lot of the decisions children make – especially the bad decisions they make. Peer pressure has always been a significant force in children’s social groups, but today, it poses an even greater risk — leading kids down the dangerous path of addiction.

Roughly 90% of teenagers have reported that they have experienced and succumbed to the pressures inflicted on them by their peers. These pressures aren’t just to skip class; rather, they are decisions that could potentially cause mental or physical harm.

75% of high schoolers state they have tried an addictive substance, and over half of them continue to use these substances today. The truth of the matter is that peer pressure is tempting more and more kids to pull on the thread of their lives and fall to the use of addictive substances.

Children have a most intense desire to be accepted by their peers; they seek external validation from others, and unfortunately, that can cause them to do things they don’t understand the true gravity of. They want to belong, which can lead them to experiment with drugs and substances they don’t know the danger of. What starts as a casual curiosity transforms into a life-altering condition that affects them and their entire community.

Addiction doesn’t exist in isolation. When it wraps itself around a child, it completely demolishes the family behind said child. The child becomes unrecognizable as their need for drugs takes priority over all in their life. They will do anything they can to get the substances they desire.

“Recognizing just how different addicts are — and how differently a son or daughter behaves once addiction has taken hold — is vitally important for the parents of addicts. As David Sheff wrote so heartbreakingly in Beautiful Boy, when addiction took over his son’s life, the boy he once knew and trusted was replaced by someone who would lie, cheat, steal, and endanger his family to get drugs. “I am in a silent war against an enemy as pernicious and omnipresent as evil,” wrote Sheff after seeing his son bounce from rehab to relapse several times. “Only Satan himself could have designed [such] a disease,” says author Jim Hight.

Navigating the convoluted reality of a child with addiction is incredibly taxing and emotionally draining. As parents and family members, it is vital to approach these children with kindness and compassion, ensuring they don’t feel isolated or attacked.

It is not easy for a parent to maneuver the addiction of their child. Oftentimes, other siblings will fall to the wayside as parents try to save their addicted child. This is why it is important to recognize that addiction is more than just one person’s suffering – it is a community’s.

“I do not have an addict for a child — in fact, I have no biological children. But I’ve watched and listened to and sat with parents of addicts, and I incorporated elements of their stories (always safeguarding anonymity) as well as those of writers like Sheff in my novel, Moon Over Humboldt. Bill, the father in my story, has to learn to detach with love from his son—a process so daunting that he doesn’t even understand what it means at first,” continues Hight.

Addiction isn’t just the burden of the one who uses substances. It is a shared struggle. The relationships that addiction harms can be rebuilt, but it requires intentional healing and a commitment to understanding the far-reaching effects of substance use within the family unit.

Published by: Martin De Juan